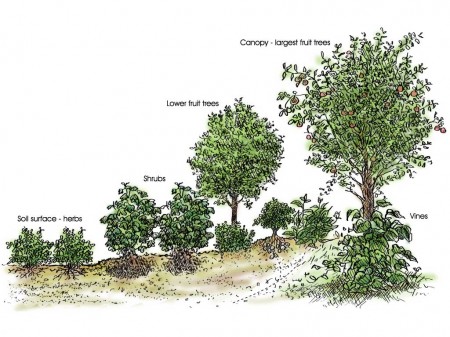

The orchard consists of various vertical levels of growth, from canopy trees to shorter trees, to shrubs and bushes, vines, herbaceous, ground cover and roots. Each level works together, offering varying degrees of shade, wind protection, support and nutrition. It takes some work and money to set it up right, but once done, it will look after itself for years to come, with very little external input.

Our forest garden is still under construction. We’ve got the first terrace planted with its trees and many of the shrubs and plants. We’ve also laid out the other terraces, and are starting to terraform them. This is a project that will take years to reach its full fruition, but even at this early stage it is contributing heavily to our daily food supply. And once it’s in full swing, we will be getting literally hundreds of different fruits, nuts, greens and vegetables for us and our animals, all without having to continually replant.

Through the course of this article, we’ll go into laying out the terraces according to contours, setting up an underground water storage battery, a two tier deep soil irrigation system, overflows, choice of plants, and other aspects of the design process. We hope the information is useful and that it encourages some of you to start your own unique reforestation project.

10 ft. 2″ PVC pipe

1x 2″ threaded cap

1x 2″ smooth to threaded (male) coupling

2x 2″ T

2x 2″ – 3/4″ reducer bushing (adaptor)

3x 3/4″ threaded nipple

2x 3/4″ thread to hose adaptor

3/4″ irrigation hose

3x 3/4″ threaded valve

1x 2″ – 3/4″ thread reducer T

1x 3/4″ thread to garden hose adaptor

garden hose

pipe glue and cleaner

Teflon

3/4″ PVC (scraps are fine)

1/8″ emitter valves

1/8″ inline drip emitters

1/8″ hose

1/8″ Ts

hammer

several posts, lengths of rebar or sticks as markers

20 ft. clear hose (unless you have a laser level or other device)

two people

two poles, 5 feet tall

a marker pen

tape measure

Rocks or retaining wall material

branches, twigs and logs

shovels, picks, digging tools

Hand saw (for PVC)

Pruning shears (to cut hose) or strong scissors

A Forest Garden is a very unique thing. A lot will depend on the space you have available, the lay of the land, and your climate, to mention just a few variables. Perhaps the best thing to do at this point is to give you an idea of our specifics, so you can decide which pieces of information will be relevant to you, and which you will need to adapt.

Our eventual goal is to terraform our whole 10 acre property, but we’re starting with a 3000 square foot area south 0f the house. This first orchard consists of four terraces, each more or less 10 ft. by 80 ft. It’s part of a south facing hill made up of clay and rocks. Native plants include oak, juniper, and acacia, and there are many edible weeds (like lambs quarters, amaranth, and purslane) that grow wild. In an average year, we get about 25″ of rain a year mostly from June through September, with annual temperatures between 25 and 105 degrees F.

It might also help to mention some of the things that helped us decide where to put our first Forest Garden. First, we wanted to be able to see it from our large, south facing windows, but didn’t want to risk a tree ever falling on the house, so it is further from the house than the tallest type of tree that we’ll be growing. Secondly, rain water catchment is the sole source of water for our property, so we didn’t want to clog up our gutters with a bunch of leaves and such. We therefore didn’t want the house to be directly downwind of the trees. Thirdly, we wanted it to be downhill from our irrigation tank, so that watering wouldn’t require any pumps. Fourthly, we have trenches that flow through the orchard that collect runoff from the road and house area, and those trenches then overflow downhill into the big pond, in case it ever rains too much.

You also need to consider pathways during the planning stage. We have a wide path at the top of each terrace, which also serves as a swale and infiltration trench from heavy rains. There are then several paths, or steps, that connect one terrace to the next.

Once you’ve decided on the size and location of your orchard, you will have to mark it on the ground.

Soil with a high organic content stores water considerably better than bare soil, which has some definite advantages. For a start, it’s a cheaper form of water storage than making ponds or tanks. Plus, it’s right there where your trees can access it as needed, decreasing the amount of time that you will have to irrigate them.

The first layer of organic content that we’ll be adding consists of things like branches and logs. As the wood rots slowly under the ground, it will hold water, add air pockets and provide a home to all kinds of mycelium and micro-organisms. The idea is to create an organic sponge that can store both nutrients and water.

We built a 7000 gallon tank specifically for irrigating the orchards, which is filled during rain season from the house roof. We dug a trench from this tank to the orchard. In this ditch we laid a 3″ pipe that connects to the tank’s overflow (so that when it’s full, its excess will feed the orchard), as well as a 2″ pipe from the irrigation tank to the main irrigation lines.

We use a two tier irrigation system. One line waters the trees and shrubs underground, so that the water goes straight to the roots without losing moisture to evaporation. The second line is a drip system that waters the plants that surround each tree or shrub spot.

Keep in mind that plumbing is a lot easier to do than explain, so even if you have no experience, don’t be put off. Looking at the photos will definitely make the descriptions easier to follow.

So, you’ve got the terrace, soil and water system ready, now what do you plant and where? That’s an impossible question to answer, as every forest garden will be different. However, there are a few guidelines to help you decide.

Forest gardens are usually divided into guilds, named for the tall tree that it will include. Each guild has up to seven layers within it: canopy tree, short tree, shrub, herbaceous, ground cover, roots and vines. You need to make sure that everything that is planted together is a companion. Some trees or plants add toxins to the soil that are poisonous to other plants, but there are always some that will tolerate it and can act as a filter to other guilds. For example, if you have a Juniper near your orchard that you don’t want to cut down, you will have to plant something like Mulberry, grapes, currants or Pomegranate next to it, as all of those are not affected by the Juniper’s toxins.

It helps to make a table with headings like: maximum height, width of canopy, temperature range, humidity range, soil preference, nitrogen fixer or feeder, companions and antagonists. Add any plant that you want to the list on the table, and fill out all the categories. There’s a lot of information out there on all kinds of options for your forest garden, but a fairly good place to start is pfaf.org

It helps to make a table with headings like: maximum height, width of canopy, temperature range, humidity range, soil preference, nitrogen fixer or feeder, companions and antagonists. Add any plant that you want to the list on the table, and fill out all the categories. There’s a lot of information out there on all kinds of options for your forest garden, but a fairly good place to start is pfaf.org

You want to mix and match your guilds, so that you balance out your tall trees and have a nitrogen fixer periodically. Include some plants that will survive extremes in temperature and humidity (weather is becoming increasingly unpredictable). Put sprawling trees like figs where you want a wind block, arbors with grapes where you want shade in summer but not winter (like over a bench), brambles like blackberries are great for hedges where you don’t want people or animals to walk.

Also, include your animals in the process; a forest garden can provide for a lot more than just you. What do your bees, rabbits, pigs like? There are many plants, like a Mulberry tree, whose leaves are edible to animals, so they end up being extra efficient food sources. You can also tractor your rabbits within the forest, so they can eat down grass and weeds, but also fertilize the soil (rabbit manure is an excellent fertilizer that can be placed on plants directly without burning them). If you have an area enclosed, you can put something like quail in there, to keep bugs down (not chickens, as they’ll scratch everything up and eat many of your plants). Do not, under any circumstances, let goats anywhere near your forest garden!

Don’t remove native trees or plants just because you might not want them in your longterm forest. Existing trees will offer shade and wind protection for tender, young plants, and the natives are already naturally adapted to your environment. You can always remove them later once things get established. Furthermore, there are many hardy weeds that are edible and tasty. Amaranth leaves, Lambs-quarters and purslane are frequent additions to our dinner salad, and many others besides are fed to our rabbits. Keeping some native weeds might also help with bug control; we noticed that grasshoppers always eat the wild amaranth first, so we started to cultivate it as a garden and orchard perimeter.

Bare in mind that many perennials take a long time to grow from seeds. If you haven’t yet found all the plants you want or your seeds haven’t grown enough, don’t be afraid to stick some annuals in there for the time being.

Forest Gardens are a continual process, so don’t think of them as a destination, but a long journey. Each year you can see what works, and adjust your layout over time. Once your initial terraforming is complete, the Forest Garden will require very little in terms of labor. As you slowly expand and perfect your forest garden, you’ll be building a permanent alternative to annual farming.